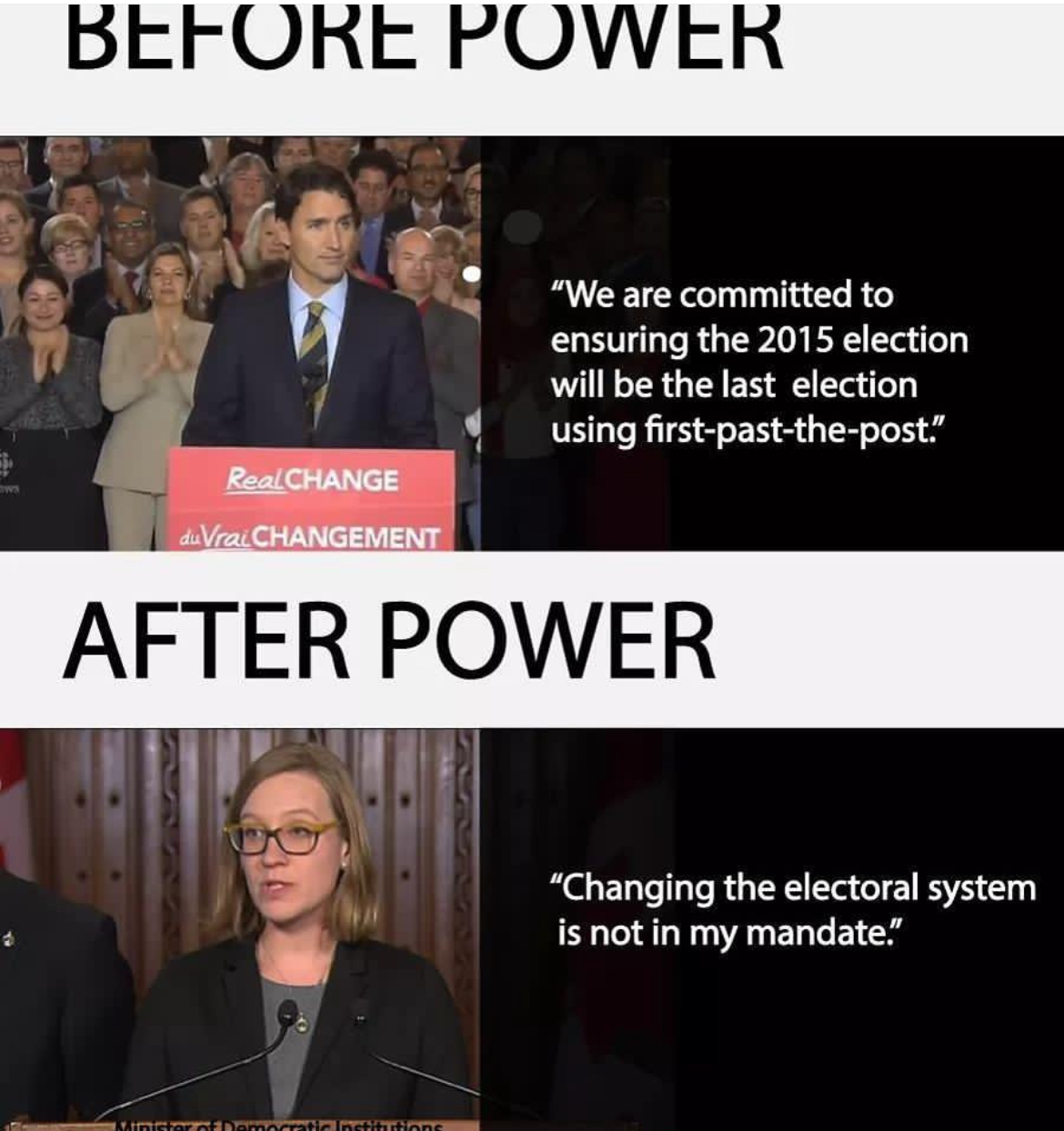

Remember when the Liberals also promised the 2015 election would also be the last under FPTP?

They kind of go hand in hand though

Not really. You can have one without the other.

My main concern with general politics posts is that they will dilute the core message of PR.

We also need general politics posts to grow the movement to new people who have never heard of proportional representation before. I've generally tried to keep topics to democracy, or from PR supporting parties, or PR itself. It's not like there are no rules.

Too much “clutter” in people’s feeds might also cause the people who are most interested in PR to unsubscribe.

This isn't what I've found to be the case based on the community statistics I've been tracking every day. The data suggests more activity consisent with what I've mentioned earlier (topics to democracy, or from PR supporting parties, or PR itself).

I'm sorry that you believe this is not what the PR community needs, but if you can come up with more PR content, by all means post them to the community. I'm just a volunteer, so you really shouldn't be expecting anything from me for a free service.

If we had proportional representation, we could vote for parties that took serious action. Instead, we're still playing this same broken game.

The comparison to Kormos is apt - both were/are principled politicians who sometimes found themselves at odds with party leadership while maintaining strong connections to working-class voters.

Leadership races are fascinating because they represent those rare moments when party members directly influence their party's direction. The 2017 NDP leadership race was particularly significant with four distinct visions for the party's future. Angus represented a return to labor-focused progressive populism that might have positioned the NDP differently in our political landscape.

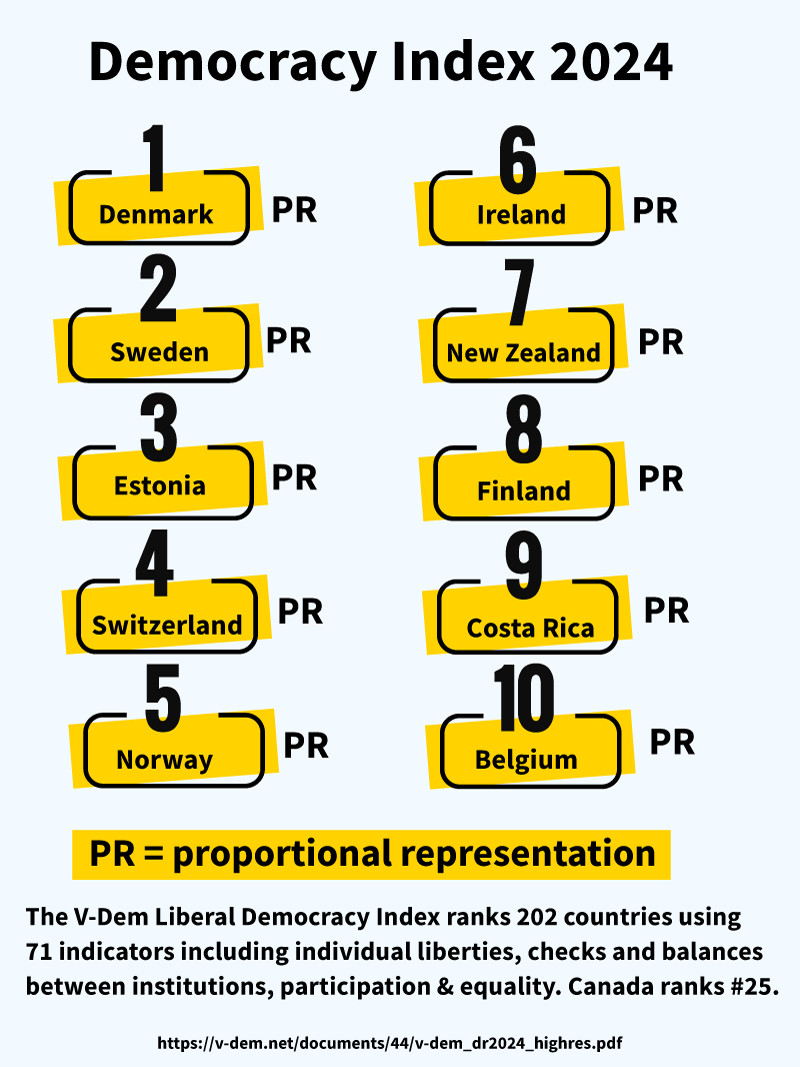

What I find interesting is how much our First-Past-The-Post system shapes these leadership decisions. Parties feel pressured to select leaders they believe can "break through" rather than necessarily representing their core values. Under proportional representation, parties would be freer to choose leaders who authentically represent their vision without the strategic calculation of "electability" in swing ridings.

The NDP's consistent support for proportional representation is one thing I appreciate about them, regardless of who leads the party.

You raise an excellent point about the value of difficult conversations in policy-making. It's refreshing to see some retirees willing to contribute solutions rather than politicians making assumptions about what people will or won't accept.

This approach of actually consulting citizens on tough choices is exactly what good governance should look like. The idea that wealthier retirees might voluntarily accept reduced benefits to help both poorer seniors and younger generations demonstrates the kind of intergenerational solidarity we need.

But you've identified exactly why this rarely happens - our electoral system creates perverse incentives. Under First-Past-The-Post, politicians focus on winning pluralities in individual ridings rather than building consensus. The result is exactly what you described: avoiding reasonable but potentially unpopular conversations at all costs.

In countries with proportional representation, we see more of these nuanced policy discussions because parties don't have to appeal to the mythical "middle voter" in every riding. They can be honest about trade-offs and still maintain representation.

The conversation about retirement benefits is precisely the kind that gets distorted when politicians are forced into binary positions by our winner-take-all system.

- Almost certainly, they have tabling booths with many print-outs. Here is a link to their Media Kit.

- Also see: Simple things you can do right now, to grow the proportional representation movement—so we never have to vote for the lesser of the evils, have a two party system, "split the vote", or strategic vote.

- If you want higher quality images, message me directly!

Your framing mischaracterizes what actually happens in both systems. FPTP doesn't produce "moderate parties" - it forces diverse viewpoints to consolidate within fewer parties where extremist elements can gradually capture them from within.

Let's examine Canada's own history: The Reform Party didn't disappear because FPTP "moderated" it. Rather, the Reform wing ultimately took over the merged Conservative Party. Stephen Harper came from Reform to lead the CPC and become Prime Minister. This pattern isn't moderation - it's the Reform ideology successfully gaining control through internal capture rather than standing alone. The same pattern happens in other FPTP countries - extremist views don't vanish; they work to take over major parties.

Your question about tensions "boiling over" assumes these tensions don't exist in Canada, rather than recognizing they're channeled differently. In PR systems, when segments of the population hold certain views, they can express them through parties that specifically represent those positions. In FPTP, these same views still exist but must operate within big-tent parties to have any chance at representation.

The key difference isn't in whether tensions exist but in how transparently they're represented. In Germany, the AfD's support is visible and proportional, while the remaining 77% can form governments that reflect majority viewpoints. This creates accountability - we know exactly how much support extremist views have, no more and no less.

As for whether 1/5 of Canadians might vote for a far-right party - that's exactly why democratic principles matter. The purpose of elections isn't to suppress certain viewpoints by design but to accurately represent citizens' actual preferences. A democracy worthy of the name trusts its citizens and ensures representation proportional to support, whatever that support may be.

What PR provides isn't the amplification of extremism but transparency and containment. It's showing us the photograph rather than retouching it to look nicer. And there's considerable evidence that this transparency leads to better long-term democratic outcomes than pretending divisions don't exist until they capture entire mainstream parties.