So you’ve never made mead before, or you’re curious what it is.

Mead is an ancient drink, with three basic components: water, yeast, and honey.

In the grand scheme of things, mead is more closely related to wine than things like beer, cider, or hard alcohol.

Some fancier names for some fancier things.

All variations below take the three simple ingredients and twists them(some slightly, others more so).

Traditional - water, honey, yeast. The bog standard, it’s a classic. It’s also delicious.

Metheglin - water, honey, yeast, herbs. This might be a weird Welsh word bastardization from which the word medicine derives. I haven’t bothered to dig deeper, but I like the story.

Melomel - water, honey, yeast, fruit. This is another very popular variety of mead. Fruit additions bring with them their own fun things, and can possibly contaminate a brew. Some like to add them in primary, some in secondary.

Pyment - water, honey, yeast, grape juice. Or maybe no water at all. This is what happens when wine and mead have a baby.

Braggot - water, honey, yeast, wort (the fermentable sugars made in beer making). I have not made this variation personally, so I will defer to others’ knowledge.

Acerglyn - water, honey, yeast, maple syrup. Some of the honey is removed, and replaced with maple syrup.

Bochet - water, caramelized honey, yeast. This is accomplished by heating the honey and boiling it. This does change some of the sugars into unfermentable ones.

Capsicumel - water, honey, yeast, chili(s). I really like this one because it’s just kind of a weird flavor to me. Spicy drink!

Cyser - water, honey, yeast, apple juice. This replaces some or all of the water for apple juice. Like if a cider and a mead had a baby.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, just getting a party started. In fact, you can mix and match and make a crazy sounding thing like a cyser bochet. Ultimately, it’s up to you to decide what you want to brew. Speaking of.

Honey Varietals

There’s so many varietals of honey it’s truly bananas.

There’s clover, wildflower, orange blossom, mesquite, blueberry, raspberry. The list is truly spectacular.

For the bulk of my recipes I use orange blossom honey. It’s a very pleasant flavor, and the only traditional mead I’ve really enjoyed.

Making Mead

A comfy list of things with which to brew mead:

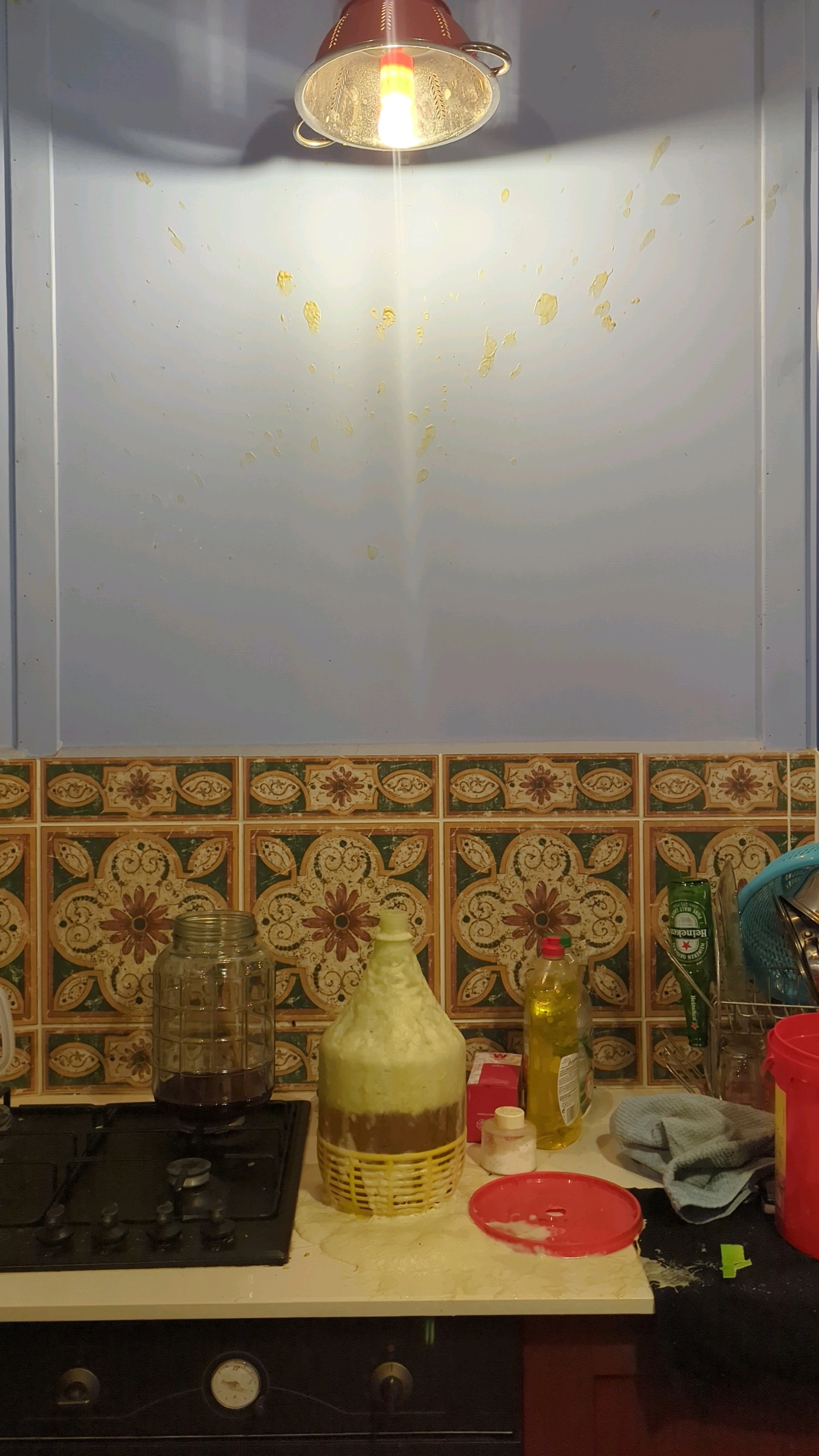

1-2 fermenting carboy (or one carboy and a pitcher, whatever will hold a gallon (4L)of water, and can be sanitized).

A bung

An airlock

Honey

Water

Yeast(I use Lalvin 71b for most things).

Yeast nutrient (GoFerm, Fermaid O, Fermaid K)

Sanitizer

Racking wand

Hydrometer - if possible have a second, they are fragile.

Graduated cylinder for the hydrometer.

Some kind of pipette / wine thief.

Corks

Hand held cork press

Bottles - five one liter bottles for a one gallon recipe, just in case.

The process:

Always sanitize everything, as per your sanitizer’s rules.

Honey in fermenter.

Water in fermenter, shake it all up. This accomplishes a few things. It puts the honey in suspension so the yeast can eat it, and puts some oxygen into the mix so the yeast can do their part.

Take a measurement. Nearly fill your cylinder using your wine thief, and (CAREFULLY) set in your hydrometer. It should read around 1.100 if you’re going along with the recipe at the bottom.

Pitch the yeast in (there’s a cool thing called GoFerm, follow those packet instructions if you went that route).

Bung in carboy, sanitizer in airlock, airlock in bung, carboy in a dark space. This is called primary fermentation.

Wait, measure every 5-7 days. Sanitize your thief and cylinder and hydrometer, steal, fill, measure.

If you’re using yeast nutrient, add it at each 1/3 of sugar consumption.

Fermentation is complete when your hydrometer reads 1.000 or lower. This means that the fermentable sugars have all been consumed by the yeast. It takes roughly two weeks to reach this stage, but there’s a buttload of variables in your environment.

You should see a pile of blech at the bottom of the carboy. The fancy name for this is lees (pronounced like lease).

This is the step that got me in trouble. You need to sanitize a second vessel (can be a carboy, bucket, or jug, depending on the size you’re brewing). Use the racking wand to transfer the mead (called racking) to the second vessel to get it off the lees.

Repeat step 5. This is secondary fermentation.

Now the long haul. Wait. The longer you wait, the better it gets. The flavors all kind of melt together. I find that after about 6 months things stop tasting “hot,” then you move on to bottling.

There’s a thing about clear mead being best. I don’t particularly care, or use any fining agents to make it clear. Most meads clear with time unless they’re super fruit laden.

Most racking wands come with a bottling attachment. Sanitize bottles, use the bottling wand to put the mead in the bottles, and cork away.

Note: this will be an unsweet mead if you bottle it at this point.

Backsweetening:

This is a slightly unfun area. You have a problem. You’ve racked your mead, you’ve taken it off the lees. It’s clear, it’s ready for bottling. But it needs to be sweeter.

There’s still some yeast in there, and adding more sugar might just make them wake back up and kick us back to primary fermentation.

In a sealed vessel, this can be a pressure bomb.

So, we need to make sure that: the yeast are truly dead and gone, or they cannot eat the sugars we’re back sweetening with.

Ways to stop the yeast:

Potassium Sorbate. This stops the yeast from dividing.

Campden Tablets. These are sulfites that prevent acetic acid (vinegar) or wild yeast that can spoil the wine.

I use both in conjunction because, well, bottle bombs are scary. I can add links but the two from brewer supply company have instructions on them.

A filter. There’s a fancy weird micron filter thing that I haven’t personally messed with, but I’ve heard that it may be able to filter out the yeast? I’m not entirely sure, I’ll leave it for someone else’s knowledge.

Figuring out how much honey to add requires some math.

There’s dry mead from 0.099 to 1.006

Medium goes from 1.006 to 1.015

Sweet goes from 1.0015 to 1.020

And dessert is anything higher than that.

Now for the math!

Honey is 35 pts/lb/gal. So if your mead is 1.000 and you would like it to be 1.011, you need to get how many points you need.

So 1.011 - 1.000

You need 11 gravity points.

Divide 11 by 35

That gets you 0.31 pounds per gallon of water.

So, if it’s a five gallon batch, you’d need to add 1.5 pounds of honey after stabilizing.

So, stabilize as per directions (most also want a 24 hour delay for efficacy).

Add the requisite amount of honey.

Gently mix, and bottle / leave to age some more.

The bare minimum setup:

1 gallon of spring water in its own container

3 pounds of honey

Bread yeast

A glove

The container that the water comes in should be sanitized from its own manufacturing, just make sure it’s a new container with the seal intact.

Pour out some of the spring water (enough to fit all the honey in). Shake the crap out of it. Poke a hole in the glove’s tip to let the CO2 escape and pray nothing creeps in. There are other ideas for home made airlocks, I’d trust a blow off tube more than this. This is just the absolute minimum to get a brew going.

Wait for awhile, carefully pour it off the lees after about a month (you’re not measuring to see when fermentation is complete). Cap the container instead of glove it. Wait some more time (still about six months). Pour it into a glass, and enjoy.

First Mead:

~1 gallon of water.

3 pounds of orange blossom honey

Yeast of choice

Other bits, bobs, and explainers:

-

Why yeast nutrient?

Honey is kinda naturally anti-microbial growth, and we want to have microbial growth. The yeast nutrient helps our little bugs eat all the sugar.

I’ve heard from various people that they can tell when the yeast had a hard time.

-

What’s with adding the nutrient in bits, can’t you just do it all at once?

You can add it all in at once, I’ve done it, the problem with that is they’ll use it all up, blow up their population, and then go back to struggle bus to ferment the rest of it.

- How do you keep track of all this stuff?

To be honest, I have a Google sheet of brews going currently and brews that are completed. I can add an image of it in future.

I’ll add more answers as people have questions.

This is a general guide, and I’m just a hobbyist.

Edit: some bits are janky, I’ll fix it in a bit when I’m at my actual computer.